Our articles

money

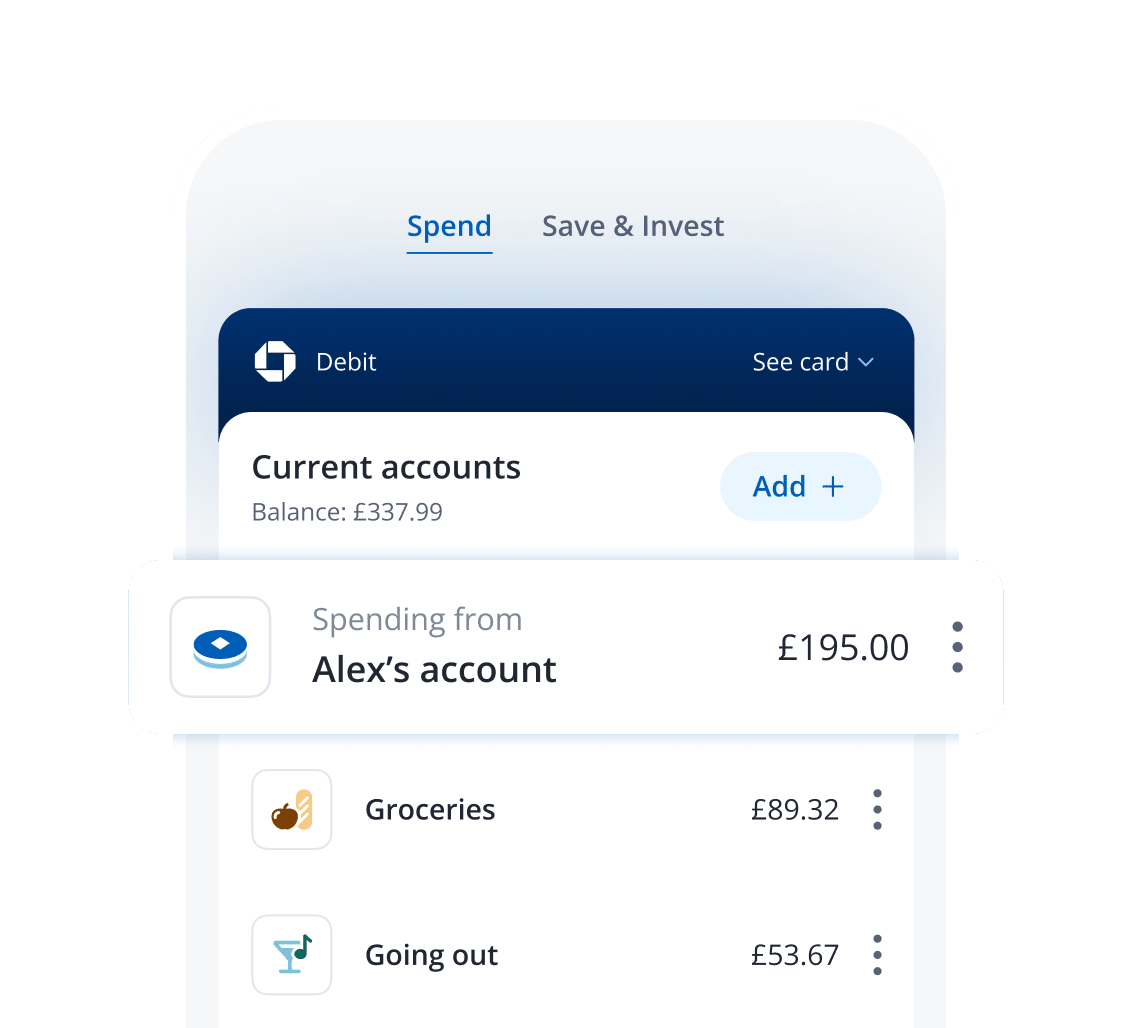

5 ways you could get the most out of your current account

4 min

money

5 humble habits to help build serious savings

4 min

Kakeibo: The Japanese art of budgeting and saving money

5 min

What is cashback and how does it work?

4 min

Don't let your digital footprint become a way for fraudsters to steal your identity

4 min

What does it take to become an ISA millionaire?

5 min

Open a free current account

Join millions of people who already bank with us.